What is the likelihood of confusion with trademarks?

In the most simple terms, ask yourself, could a consumer confuse your products or services with a similarly named brand’s? If so, then you likely have a likelihood of confusion.

A common reason that the USPTO refuses trademark applications is due to a “likelihood of confusion” between the applied-for trademark, a registered trademark, or prior-filed pending trademark. Trademark law (Section 2d) prohibits the registration of a trademark application that is too similar to a registered mark. If consumers would be confused, mistaken, or deceived about the original source of the goods and/or services, a likelihood of confusion exists. The likelihood of confusion is determined on a case-by-case basis by analyzing “du Pont factors”. Any evidence related to those factors needs to be considered; however, not all of the du Pont factors are relevant for every case.

There are generally two key considerations in any likelihood of confusion analysis:

(1) the similarities between the compared marks; and

(2) the relatedness of the compared goods and/or services.

Again, the USPTO will deny an application based on the conclusion that the applicant’s trademark has similarities to a registered mark if it can cause consumer confusion. This does not mean your business, brand, logo, or slogan has to be an identical match to existing pending/registered trademarks. In fact, they can be quite different in many ways. It is much easier to receive a likelihood of confusion refusal than many would suspect. The trademarks only need to be similar in spelling, pronunciation, or consumer impression. Minor differences (making a word plural, changing spacing or spelling, etc.) do not tend to matter if pronunciation or interpretation would or could be similar.

Source: e.g., Federated Foods, Inc. v. Fort Howard Paper Co., 544 F.2d 1098, 1103, 192 USPQ 24, 29 (C.C.P.A. 1976) ; In re Iolo Techs., LLC, 95 USPQ2d 1498, 1499 (TTAB 2010); In re Max Capital Grp. Ltd., 93 USPQ2d 1243, 1244 (TTAB 2010) ; In re Thor Tech, Inc., 90 USPQ2d 1634, 1635 (TTAB 2009).

Trademarks need to be very distinct and different from other trademarks.

If a business applies for a trademark that is similar to a registered mark the later filed marks will likely be denied. Trademarks are highly coveted because it gives you exclusive ownership over words or a logo in connection with specific products or services. Simply ask yourself, “as a potential consumer, could I be confused to think the two businesses were associated?” Brand names can have identical names in different classes and unrelated industries. For example, there are existing registered trademarks for Delta® as an airline company and Delta® as an unrelated faucet brand. A consumer is unlikely to believe Delta®, the faucet brand, is suddenly entering the airline industry, so this is allowed by the USPTO. Many additional elements of a trademark are examined such as industry, the fame of the existing marks, if actual confusion has occurred, impulse buys (example: screen protector) vs. careful, sophisticated purchasing (example: a car), etc. You’ll want to have a distinct name within the industry to give yourself the best protection.

Source: TMEP §1207.01(d)(vii)

Can I make minor edits to the word to make my trademark distinct?

Adding a word or letters to a registered trademark generally does not get remove the similarity between the compared marks, nor does it overcome a likelihood of confusion under Trademark Section 2(d). For instance, it would be nearly impossible to register Apple Tech for anything in the technology, when Apple® already has an existing famous trademark. There would be a likelihood of confusion.

Further, incorporating the entirety of a trademark mark within another does not remove the similarity between two similar marks. For instance, a business’ application would be denied for Lit Nykee Sportswear, because the Nike® and Nykee could potentially be pronounced the same, and further, the entire mark, Nike, is incorporated in the applied-for mark.

Source: Coca-Cola Bottling Co. v. Jos. E. Seagram & Sons, Inc., 526 F.2d 556, 557, 188 USPQ 105, 106 (C.C.P.A. 1975) (finding BENGAL LANCER and design and BENGAL confusingly similar); TMEP §1207.01(b)(iii).

Lastly, you cannot remove a word from a registered trademark, in a similar industry, and be approved. For instance, if you wanted to trademark Star as a coffee shop, the USPTO would likely refuse your application for a likelihood of confusion with Starbucks®. Even if the USPTO initially approves the name, Starbuck’s legal team would swiftly come knocking on your door. The shortening of the name would not prevent the likelihood of confusion. Even if a trademark does not contain the whole brand name of a registered trademark, the shortened version is likely to appear to prospective purchasers as a shortened form of the registered trademark.

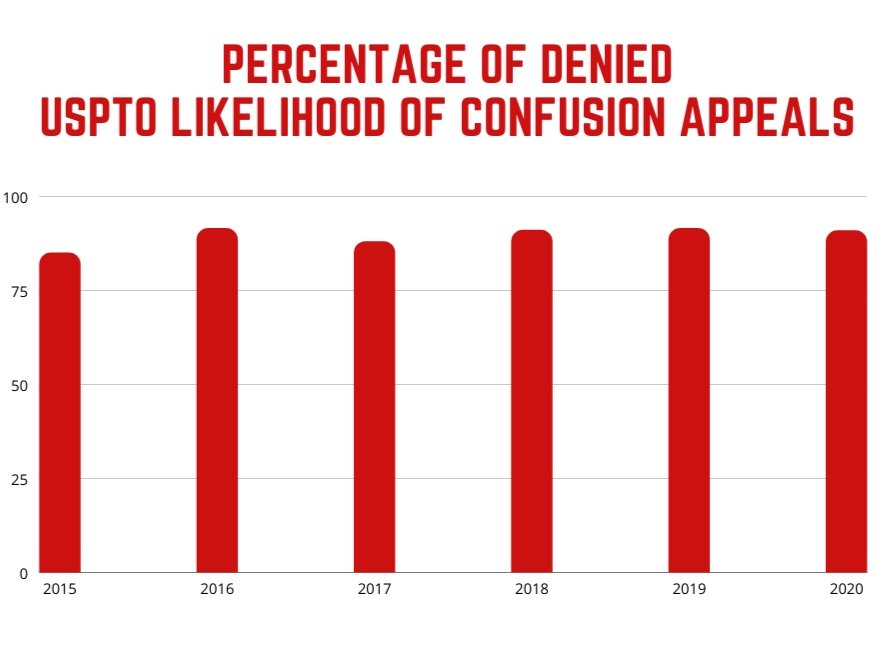

It is always best to get an experienced attorney to run a comprehensive search to increase your chances of getting your trademark accepted by the USPTO and registered. If you do happen to receive a refusal, be aware the odds are against you in filing an appeal.

Over the past 10 years, the USPTO has only accepted around 11% of appeals for the likelihood of confusion. Unless you are very attached to your intended trademark, or have spent thousands branding your products, it is often more cost-effective to rebrand.

To find out how to pick a strong trademark name, please visit my blog post on that topic.

To have a comprehensive search of a trademark, please visit my services page.